Those who have been following me for a while will be aware that I have previously written three blog posts exploring the stars of Castor and Pollux. The first one was titled “Fixed Star Astrolatry: Capella, Alphard and Castor” published on July 2022, the next titled “Castor and Pollux: A Deeper Dive” published on November 2022, and the final titled “O Light, Enduring: Meditations on Hope and the Winter Sun” published a month later. I have chosen to take these articles down in order to compile them, along with some of the more recent revelations, into one comprehensive post. Frankly, I also felt that I have outgrown those older articles so to speak, and this is my way of updating my blog with some new things I’ve learnt. So, I hope that this post is useful to anyone interested in venerating or learning more about the Gemini twins.

The post will be split into two parts. First, “The Twin Myth: A Quick History of the Stars”, being a quick review of the mythology and folklore associated with the stars. The second part, “Twin-Star Astrolatry: Interpretation and Veneration”, being a more subjective write-up of my own UPGs of the stars as gleaned from my experiences working with them.

P.S. Before anyone says anything, I know my citation methods are kind of messed up because technically I should be citing page numbers when making direct quotations, and that I’m using way too many direct quotations for what would be allowed in academia. But, frankly, this is a blog post not an academic paper, and I may have lost track of some of my sources at this point… so lol. Make of this blog post what you will.

The Twin Myth: A Quick History of the Stars

The classic Greek myth often told of Castor and Pollux’s origin is as follows:

Leda was the beautiful daughter of Thestius and Eurythemis, married to King Tyndareus of Sparta. Zeus caught sight of Leda and became immediately attracted to her. Knowing that Leda was fond of animals, he disguised himself as a beautiful white swan and then had the eagle pursue him. As he flew over Leda and caught her attention, Zeus — in the form of a swan — pretended to be injured and landed near her. Leda rescued and comforted the swan, and drove the eagle away. It was then at which Zeus took the opportunity to seduce Leda and it soon became apparent that Leda was pregnant. Instead of a normal child, Leda delivered two giant eggs. These eggs soon hatched and revealed two pairs of nonidentical twins. In one egg, there was Polydeuces (Pollux), and his sister Helen. In the other egg were Castor and his sister Clytemnestra. Castor and Clytemnestra were the children of Tyndareus, while Pollux and Helen were the children of Zeus (Simpson, 2012).

As they grew up, Castor and Pollux were inseparable. They became close friends with their twin cousins Idas and Lynceus. The two cousins then joined Castor and Pollux on the expedition of the Argonauts to recapture the golden fleece. Later, the twins and the cousins joined a raid to steal a herd of cattle. After this raid, Idas was chosen to divide the spoils. He set out four portions of meat and ruled that half the cattle would go to the person who finished eating his portion first, and the remainder to the one who finished second. While the meat was being divided, and before the others were ready to begin, Idas bolted his portion, and then helped Lynceus finish his before either Castor or Pollux could finish. Feeling cheated, Castor and Pollux waited until Idas and Lynceus were away, and stole the cattle for themselves. When they heard that their cousins had returned and were planning to retaliate, they hid and lay in wait to ambush them. The ambush was foiled when the Lynceus spotted them, and a pitched battle ensued (Simpson, 2012).

In the outcome of the battle, Castor and Lynceus were killed, and Pollux was left severely injured. But before Idas could kill Pollux, Zeus stepped in to protect his son and slew Idas with a thunderbolt. As the son of Zeus, Pollux was immortal. Pollux therefore pleaded with Zeus to either return Castor to life, or to allow him to join Castor in the underworld. Yet, even the mighty Zeus lacked the ability to return people from the underworld realm of Hades. In the end, Zeus negotiated a compromise in which the two twins could be together again, with both spending half their time in the heavens and half in the underworld. This supposedly explains why the twins exist above the earth only for half the year, and below the earth and invisible for the other half, holding hands so they can never be separated again (Simpson, 2012).

But there are other versions of the myth:

An old legend has Helen as child of Nemesis; the egg she is hatched from is brought by Hermes to Leda who acts as a surrogate brooding-hen. This is possibly why D’Arcy Thompson, author of A Glossary of Greek Birds, suggests that Leda was originally herself a swan who was attacked by an eagle (Ahl, 1982). It was through myths such as these where authors such as Ahl (1982) points out the Leda myth is one that involves much ‘twinning’. Two different birds are associated with her, presumably one that is originally male (the eagle), and the other originally female (the swan). There are two sets of twins: one male (Castor and Pollux), one female (Clytemnestra and Helen). Castor and Pollux are brothers, one immortal, one mortal, alternating between the light of the world above and darkness of the world below. It is with this line of thinking that Ahl (1982) argues that if the eagle and swan were not but rival symbols of light, but rather that of the light and the banished light. Thus, it could be argued that the twins Castor and Pollux represent a form of duality.

To the Greek and Roman, Castor and Pollux were venerated as the Dioskouroi. As the Dioskouroi, depictions of the Castor and Pollux in Roman art associate them with the Sun and the Moon. The Dioskouri could be seen wearing on their caps images of the Sun and the Moon, thereby painting Castor and Pollux as guardians of the day and the night hemisphere, of Heaven and of Hades, or as guardians of the two celestial hemispheres divided by the equinox and, at the same time, as personifications of the Sun and the Moon. However, to say that Castor and Pollux are mere personifications of the opposing forces that make up the universe would be reductionistic. Castor and Pollux represent not just the dichotomy of the cosmos, but also its integrity and harmonic unity. The dokana, a symbol of the Dioskouroi, is made up of two upright columns which represents the heavenly twins as pillars ensuring the stability of the cosmos, along with cross-beams which symbolizes their unity and, by extension, ‘the concord in the cosmos, as opposed to the anarchy of the chaos’ (Coucouzeli, 2006).

The concept of duality is also present in the constellation of Gemini, wherein the constellation is associated with Apollo and Heracles respectively. Hyginus and Ptolemy associated Gemini with Apollo and Heracles, and there also exist several instances where the heavenly twins are depicted carrying the characteristic attributes of Apollo and Heracles, such as a bow and/or an arrow and a lyre, and a club. This could be seen on the Zagora seal, for example, where the left-hand figure resembled Castor/Apollo, while the right-hand figure depicts Pollux/Heracles. This practice of associating Apollo with Castor and Heracles with Pollux continued into the relatively more modern time period. European celestial atlases dating from sixteenth to eighteenth centuries likewise continued to mark the twins as ‘Apollo or Castor’ and ‘Heracles or Pollux’ (Coucouzeli, 2006). Castor’s connection to Apollo is also present in the very name of the star. According to Star Names: Their Lore and Meaning by Richard Allen, Castor was called Apellon in the Doric (Greek) dialect, and the name later degenerated into Afelar, Aphellon, Aphellan, Apullum, Aphellar, and Avellar [when translated to Arabic]. In the 16th century, the name subsequently appeared as Anelar as well (Allen, 2000).

Many ancient societies from various continents all across the globe appeared to have developed their own version of a celestial twin myth. In particular, a cult of divine twin healers appears in a wide belt stretching from ancient India to the Mediterranean. The most well known of this would be that of the Vedic Ashvins who are the twin healers and physicians of the gods, often depicted in the form of divine horsemens. The Ashvins are said to be able to perform extraordinary medical feats including the resurrection of the dead, the restoration of sight to the blind, helping the lame to walk again, replacing a head which has been cut off, and providing prostheses for amputated limbs. Additionally, the Ashvins also assist in childbirth and hellp restore the aged and impotent to full vigor. It could be surmised that they are the inventors of medicines and the ones who taught mankind the healing arts (Hankoff, 1977).

All in all, the Ashvins could be described as saviors of mankind. More literally, they are known to have snatched from danger those who call on them for help, such as by freeing men who have been captured by bandits, saving men from drowning, and rescuing another from a burning chasm (Hankoff, 1977). This role of the Ashvins as being saviors of mankind is similar to the Dioskouroi’s epithet of soteres. According to Homer, Pollux and Castor are ‘savior-children of men upon the land and ships upon the sea, when the wintry winds rage over the savage deep’ (Rothrauff, 1966). The Dioskouroi are said to appear to sailors in times of danger in the form of two stars, or in the form of a phenomenon known as St Elmo’s fire (Hankoff, 1977). St. Elmo’s fire, also ominously called the Witch’s fire. St. Elmo’s fire is named after St. Erasmus of Formia, the patron saint of sailors. Those who sail among stormy seas often view the phenomenon to be a good omen as it often warns of an imminent lightning strike, promising the sailors that they will escape unharmed despite the dangers. In the 15th century, Admiral Zheng He had inscribed a reference to the phenomenon, claiming that “in the midst of the rushing waters it happened that, when there was a hurricane, suddenly a divine lantern was seen shining at the masthead, and as soon as that miraculous light appeared the danger was appeased, so that even in the peril of capsizing one felt reassured and that there was no cause for fear” (Dreyer, 2007).

Just as St. Elmo’s is described to be akin to a “divine lantern” as aforementioned, the Greeks of ancient times also refer to a single instance of St. Elmo’s fire by the name of Helene which literally means “torch”. The association with Castor and Pollux and fire does not end here either. In Hamlet’s Mill: An Essay Investigating the Origins of Human Knowledge And Its Transmission Through Myth, it is stated that the Aztecs took Castor and Pollux to be “the first fire sticks, from which mankind learned how to drill fire”. Similarly, in Myths of the Origin of Fire, it is said that the Tasmanians also “felt indebted to Castor and Pollux for the first fire”. Castor, therefore, represents this so-called “first fire”. It is a star of deliverance and hope. It is the light in the darkness, the warmth in winter. When the world seems dark and cold, Castor is the torch and the fire. It is a star of hope in the face of despair, hope in the face of utter annihilation. It is the Star shining above the Lightning-Struck Tower. Bernadette Brady similarly draws a parallel between Castor and Lucifer, the light-bearer. In her words: “the morning star was also known as Lucifer (light-bearer) and the evening star, Vespers (evening). Lucifer’s expulsion from heaven and into the whirlpool is possibly the mythological retelling of the slipping of Castor into southern declinations.”

Additionally, aside from the supernatural powers that both the Ashvins and Dioskouroi possess that allows them to perform miracles, another quality prominently associated with celestial twins is the ability to perform divination. The Iroquois twins, for example, are associated with the prediction of the future. The Golah of Liberia are associated with the interpretation of dreams. Similarly, the twins of the Peruvian Indians and African Zulus are known to be able to foretell the weather. This is not unlike the Dioskouroi and the Vedic Ashvins who, as previously alluded to, are patrons of travelers, wayfarers, and sailors (Hankoff, 1977).

On the other hand, when it comes to Babylonian star lore related to the constellation of Gemini, the Gemini twins are more heavily associated with the underworld and the dead. The Neo-Babylonians associated Gemini with the deity Nergal, a war god whose cult center was the city of Kutha in central Mesopotamia. From the Akkadian to Neo-Assyrian periods, his cultic presence and influence expanded throughout Mesopotamia, Syria and the Levant, and Cilicia, Cappadocia, and Anatolia. As his popularity and cult grew, he maintained his connection to war, but also came to be associated with disease, death, and eventually became ‘Lord of the Underworld’ by the mid-second millennium BC. Nergal is typically depicted as a bearded man wearing a long garment and either a flat, horned cap or a high tiara. In many Mesopotamian communities, there was a close relationship between Nergal and Nanna/Sîn, with a number of traditions identifying them as siblings/twins. Likewise, the two twin figures of Lugal-Irra and Meslamta-ea are said to be two personae of Nergal (Dandrow, 2021).

Interestingly enough, this association of the celestial twins with death can also be seen in modern times, albeit only mainly via folk practices related to the Dioskouroi. Wenzel (1967) argues that a group of rituals which are still carried on at the Serbian village of Duboko, at whose core is a fire-making ritual, is related to the rituals of the Danube tablets whose purpose is to avert danger from a living person or to secure him the help of powerful beings— namely, the Dioscuri. Similarly, it is implied that the Dioskouroi are associated with several folk dances and ritualistic practices originating in the Balkans, such as the practice of the padalice, also known as the ‘falling ones’. Wenzel (1967) believes that the purpose of the rituals of the falling ones is to remove death from a dead person through entering the otherworld as a substitute for the dead, so that deceased person may be released.

The twins’ association with death can also be potentially seen in relation to the Eleusinian Mysteries as well. In Aulus Gellius’ Attic Nights, a work of the late second century AD, it is shown how the Dioskouroi were frequently invoked in oaths, although differently by men and women (Gartrell, 2021). An explanation for this gendered exclamation may be that women’s use of oaths derives from the Eleusinian initiations to the mysteries of Demeter and Proserpina (Gartrell, 2021). Although the Dioskouroi do not appear to have been worshiped at the mysteries themselves, they were thought to have been initiates of the Eleusinian mysteries. According to Wright (1919), the Mysteries were divided into two parts: the Lesser Mysteries and the Greater Mysteries. The Lesser Mysteries were said to have been instituted when Hercules, Castor and Pollux expressed a desire to be initiated. Hence, it may not be improbable that the Dioskouroi were ‘linked in their role as companions at death or psychopomps to these mysteries concerned with the afterlife’ (Gartrell, 2021).

This theme of death associated with the twin extends too to Thai folklore, wherein the constellation of Gemini in Thai stellar mythology is represented by the “crow perched upon the coffin” (กาเกาะปากโลง), with Castor and Pollux forming a part of the coffin. The crow and the coffin is also said to have been used as a significator for good and ill omens by the villagers of Phatthalung, a southern province in Thailand (Phengkǣo, 2000). This concept of the stars of Gemini being associated with a coffin is also present in Germanic folklore. In the fairy tale of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, the seven dwarfs are interpreted to be the seven stars of the Pleiades whilst Snow White’s coffin is said to be represented by the stars within the constellation Gemini, consisting of α (Castor), β (Pollux), γ and μ Geminorum.

The concept of Castor as a spiritual psychopomp comes up again when delineating the sign of Gemini. In his article Gemini: The Search for the Missing Twin, Brian Clark comments on the myth of Castor and Pollux, stating that: ‘it is the severed connection to the twin/sibling that allows the other to cross the threshold to the underworld, the psychological territory where we encounter ‘shadow’. Castor, the mortal, becomes a psychopomp leading his brother across the liminal of death’ (Clark, 2000). If Gemini were to be viewed as a metaphor for the stage of development in the human psyche that occurs at an early age — the age before we develop our ability to reflect or analyze, before the experience of emotional attachment has been internalized — then as a symbol of the development process, it can be said that Gemini represents the mind that is too young to consciously hold the impact of a profound loss such as the loss Pollux experienced (Clark, 2000).

This grief that Pollux experienced, a grief so profound he would rather die than spend a life apart from his twin, is so immense and yet due to the inability for the grief to be integrated, the emotions are forgotten. Again, to quote Clark (2000): ‘the feelings that are constellated with this loss are consciously forgotten, flowing into the Lethe, the Underworld river of forgetting. The potent feelings of grief, awoken by the separation from the other, are interred and denied conscious access, becoming shades of feelings: a sense of emptiness, something feels missing or lost, a feeling of incompleteness’. In this light, it could perhaps be concluded that the twins’ association with the Underworld is less related to the concept of death itself, and more so the concept of loss and grief, especially with regards to loss as a form of forgetting.

Twin-Star Astrolatry: Interpretation and Veneration

From this point onwards, what I write is based upon my own subjective viewpoints and personal experience. Your experiences or understanding of the twin stars may differ, and that is perfectly alright.

My first takeaway from studying the Dioskouroi’s myth is that love is the point. There is a reason why the Lovers card in tarot is associated with Gemini, the constellation that Castor and Pollux is in. It is love that elevated Castor to the heavens: the love Pollux has for his brother, the love Zeus has for his son. Yet, although Castor was the one who died, it is Pollux who is forced into the role of the witnesser of death. It is those who are left behind to pick up the pieces who are left to mourn, left to be the ones suffering from the pain of loss. Worse than the heartache of mourning the lost love however, is the horror of realizing that in time you will begin to forget. As time goes on, you may struggle to recall the details of your loved one’s face or the memories of how they sounded when they laughed. Memories are fickle things, and it has been proven by neurologists that a memory can evolve based on retelling a story. How can you be sure then, that what you remembered is real? In time, it is hard to tell how something actually happened, only how you remembered it. The burden to maintain a connection to one’s beloved dead amid fading memories is a burden that falls upon Pollux. It is a form of necromancy, an expression of love. Hence, I associate Pollux very much with fading or forgotten memories, with grief and nostalgia— nostalgia being the wistful longing for the past.

Castor does have his parts in the remembrance of lost love too, albeit with a hopeful and heroic embellishment to the tales he writes. Castor is the bard who keeps memories alive via songs and stories, who immortalizes figures which would’ve been forgotten through time if not for the tales their descendants still tell of them. Castor turns stories into myth, transforms people into legends. To quote a line from a TV show I hold a fondness for: “You said memories become stories when we forget them. Maybe some of them become songs.” In this regard, Castor too is a being of seership and prophecy. After all, poesy and prophecy are often intertwined, and Apollo himself who is associated with Castor is the lord of songs and divination both. Castor, in my experience, is a weaver of tales and spinner of fate and an embodied spirit of divination. For this reason, it is my belief too that all magic to do with wordsmithery or storytelling falls under the purview of Castor, whether that be the Celtic draiocht ceoil, the Slavic zagovory, the Nordic seiðr or the Vedic vrata katha.

Castor, in my experience, is a star heavily associated with hope. My first foray into experiencing this aspect of Castor frankly came from playing MMORPG games, especially FFXIV: Shadowbringers and Endwalker. I then delved deeper into this by searching for poetry on the theme of hope. For astrolaters who are interested in connecting with Castor via poetry, I have selected three poems which I believe are effective for this purpose.

The first poem is Motto by Bertolt Brecht. It goes as follows:

In the dark times, will there also be singing?

Yes, there will be singing.

About the dark times.

Bertolt Brecht has Castor as his heliacal setting star, his chart having a Rodden rating of AA. This poem, in my opinion, encapsulates the nature of Castor very well. Castor isn’t blind to the darkness— he may not understand the depth of shadows the way Pollux does, but he does recognize that darkness and despair exists. Yet, even among the dark times, Castor knows that there will be hope: there will always be singing, among the dark times and about the dark times. It reminds me of my other favorite quote from FFXIV: “and amidst deepest despair, light everlasting.”

The second poem is Last Night As I Was Sleeping by Antonio Machado.

Last night as I was sleeping,

I dreamt—marvelous error!—

that a spring was breaking

out in my heart.

I said: Along which secret aqueduct,

Oh water, are you coming to me,

water of a new life

that I have never drunk?

Last night as I was sleeping,

I dreamt—marvelous error!—

that I had a beehive

here inside my heart.

And the golden bees

were making white combs

and sweet honey

from my old failures.

Last night as I was sleeping,

I dreamt—marvelous error!—

that a fiery sun was giving

light inside my heart.

It was fiery because I felt

warmth as from a hearth,

and sun because it gave light

and brought tears to my eyes.

Last night as I slept,

I dreamt—marvelous error!—

that it was God I had

here inside my heart.

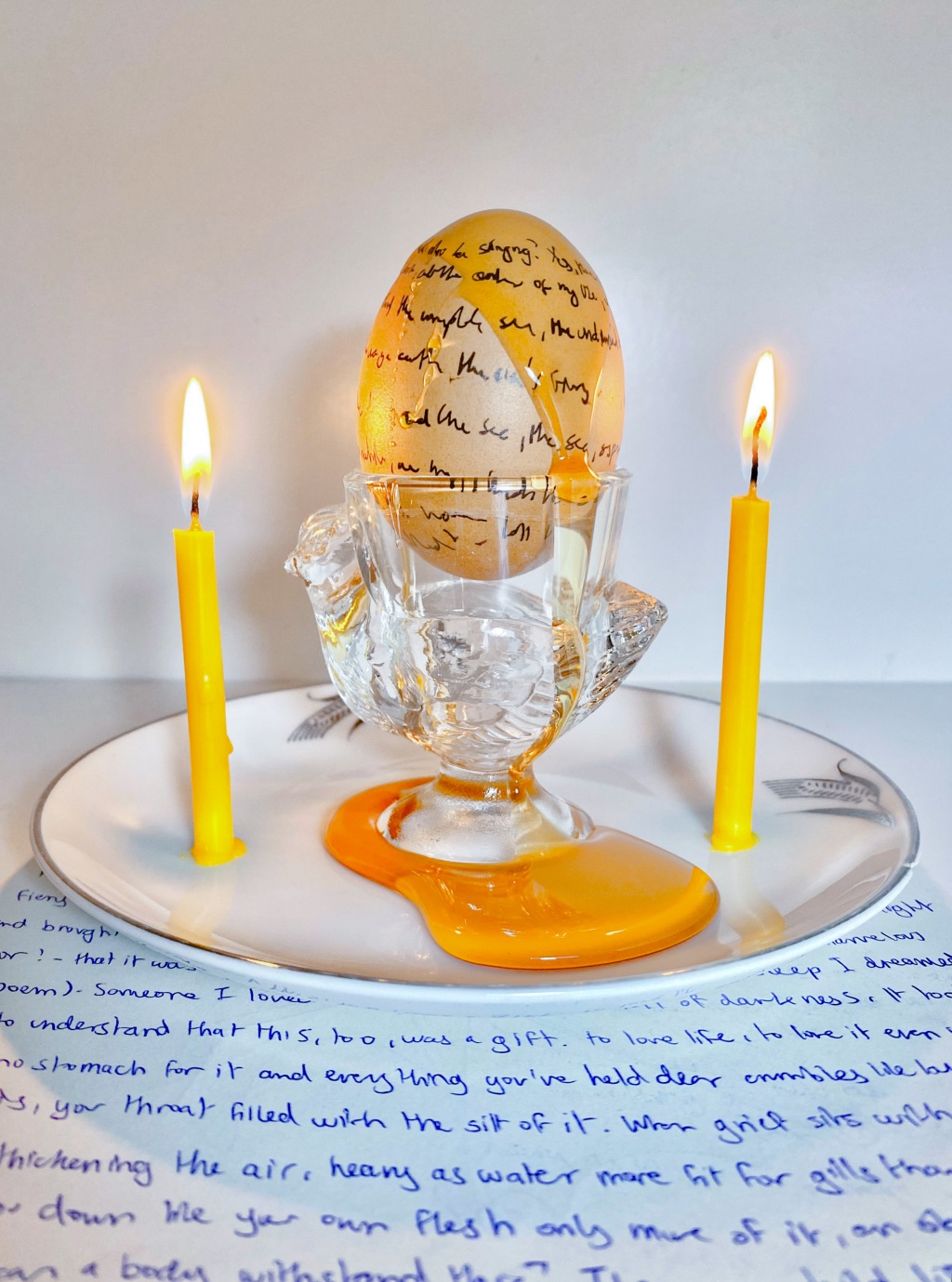

Antonio Machado’s chart has a Rodden rating of AA and he has Castor as a setting star in paran with the sun. This poem describes well my association of Castor with the human heart (the vessel which feels, which hopes and loves) and honey and bees and sunlight. It is because of this poem that I was inspired to perform rituals in veneration of Castor, wherein I poured honey over an egg (remember, Castor was born from an egg) of which I have written upon it the texts of various devotional poems.

Finally, the last poem is Ithaka by C.P. Cavafy, as translated by Edmund Keeley.

As you set out for Ithaka

hope your road is a long one,

full of adventure, full of discovery.

Laistrygonians, Cyclops,

angry Poseidon—don’t be afraid of them:

you’ll never find things like that on your way

as long as you keep your thoughts raised high,

as long as a rare excitement

stirs your spirit and your body.

Laistrygonians, Cyclops,

wild Poseidon—you won’t encounter them

unless you bring them along inside your soul,

unless your soul sets them up in front of you.

Hope your road is a long one.

May there be many summer mornings when,

with what pleasure, what joy,

you enter harbors you’re seeing for the first time;

may you stop at Phoenician trading stations

to buy fine things,

mother of pearl and coral, amber and ebony,

sensual perfume of every kind—

as many sensual perfumes as you can;

and may you visit many Egyptian cities

to learn and go on learning from their scholars.

Keep Ithaka always in your mind.

Arriving there is what you’re destined for.

But don’t hurry the journey at all.

Better if it lasts for years,

so you’re old by the time you reach the island,

wealthy with all you’ve gained on the way,

not expecting Ithaka to make you rich.

Ithaka gave you the marvelous journey.

Without her you wouldn’t have set out.

She has nothing left to give you now.

And if you find her poor, Ithaka won’t have fooled you.

Wise as you will have become, so full of experience,

you’ll have understood by then what these Ithakas mean.

Cavafy’s chart is uncertain. However, Keeley — the translator — has a chart available with an AA Rodden rating which shows that he has Castor as his heliacal setting star. I think this captures well Castor’s philosophy to fall in love with life, that life is but a journey that you should not rush. It reminds me of one of my favorite speeches from FFXIV by the character Venat who asks you “has your journey been good? Has it been worthwhile?” I have used both the poem and the speech multiple times in my devotions to Castor, and often it has left me in tears.

In my explorations of Castor and Pollux, I have come across two terms commonly discussed in the context of literature to do with psychology, mental health and palliative care: the term “will to live” and the “zest for life”. The term will to live has been defined as “the psychological expression of one’s commitment to life and the desire to continue living, encompassing both instinctual and cognitive components” (Bornet et al, 2021). It is both something that is consciously acquired and maintained, but also something that exists at an innate level within an individual. Yet, the will to live is not simply the opposite of the wish to die for both can exist simultaneously within the same person and, in some cases, an expression of the wish to die can be a cry for help, a manifestation of the will to live (Bornet et al, 2021). The co-existence of the will to live and the wish to die points towards how the desire for life and death are often intermingled. How often is the wish for death in truth a wish for the death of one’s current life, a wish for a pseudo-rebirth, for the slate to be wiped clean of the unbearable pain and for a transformative change to occur?

In contrast, the zest for life has been defined as the act of “being satisfied with different aspects of life and having the courage to look for new experiences”, and what that satisfaction means can vary from person to person (Glasberg et al, 2013). The zest for life has also been referred to as “an enthusiasm in response to life”, in contrast to the concept of apathy which reflects the thought that “nothing is worth doing” (Glasberg et al, 2013). Likewise, there appears to be a positive correlation between the “alleviation of suffering” and the “zest for life” (Glasberg et al, 2013). This would imply that although it is the will to live that prevents an individual from ending their life, it is the zest for life that makes the act of living bearable or even enjoyable. Collins et al (2018) goes on to argue that having a zest for life isn’t simply about having a positive future outlook: zest is a broader construct than optimism and hope because it also captures the current engagement with life. In other words, you are not simply hoping for a better future, but also actively living a life that brings you joy. This blend of “positive present and future-focused engagement” is arguably necessary in dealing with adversity and hardship and maintaining a sense that life is worth living, even if one’s current circumstances are less than ideal (Collins et al, 2018).

It is my conjecture that the “will to live” is a concept associated with Pollux, whilst the “zest for life” is one that is associated with Castor. Pollux, at least thematically, reminds me of the fixed star Achernar in the constellation Eridanus. In my understanding — based on Sasha Ravitch’s 2022 Astromagia talk — Achernar is associated with the callousness of life, how tragedies can occur for no reason other than sheer bad luck. Achernar is the deep, deep despair that pushes one to the brink. Achernar is thus associated with the moment where one may choose to self-annihilate or to push on, to end it all or instead be transformed by the painful experience. It is in these moments that the will to live emerges from the wish to die, that Pollux’s witchfire shines through amid the howling, cliffside storm, the “St. Elmo’s Fire” of which one may be “purified or putrefied” by (Ravitch, 2022). Pollux may be associated with depression and grief and sorrow and melancholy, but in the end, Pollux is a necromancer. Pollux is the immortal one who has never known death. He is one who subverts death, who brings Castor back to life. Ergo, Pollux is very much the representation of the will to live.

Speaking of melancholy, a historical figure whose works and life was heavily associated with melancholy is John Keats, the poet who wrote the well-known poem of Ode to Melancholy. For obvious reasons, although I believe this poem can be used for Pollux veneration, another poem that instead caught my eye and made my senses tingle in ways I could not explain is Keat’s poem of Isabella, or the Pot of Basil. The plot of the poem, as summarized by Wikiepdia, is as follows: “it tells the tale of a young woman whose family intend to marry her to ‘some high noble and his olive trees’, but who falls for Lorenzo, one of her brothers’ employees. When the brothers learn of this, they murder Lorenzo and bury his body. His ghost informs Isabella in a dream. She exhumes the body and buries the head in a pot of basil which she tends obsessively, while pining away”. The poem is too long to be pasted onto this blog without taking up considerable space, but it can be easily found online for those who wish to read it. The following four stanzas, however, resonate strangely with me, in ways I cannot easily put into words:

Then in a silken scarf, – sweet with the dews

Of precious flowers pluck’d in Araby,

And divine liquids come with odorous ooze

Through the cold serpent pipe refreshfully, –

She wrapp’d it up; and for its tomb did choose

A garden-pot, wherein she laid it by,

And cover’d it with mould, and o’er it set

Sweet Basil, which her tears kept ever wet.

And she forgot the stars, the moon, and sun,

And she forgot the blue above the trees,

And she forgot the dells where waters run,

And she forgot the chilly autumn breeze;

She had no knowledge when the day was done,

And the new morn she saw not: but in peace

Hung over her sweet Basil evermore,

And moisten’d it with tears unto the core.

And so she ever fed it with thin tears,

Whence thick, and green, and beautiful it grew,

So that it smelt more balmy than its peers

Of Basil-tufts in Florence; for it drew

Nurture besides, and life, from human fears,

From the fast mouldering head there shut from view:

So that the jewel, safely casketed,

Came forth, and in perfumed leafits spread.

O Melancholy, linger here awhile!

O Music, Music, breathe despondingly!

O Echo, Echo, from some sombre isle,

Unknown, Lethean, sigh to us – O sigh!

Spirits in grief, lift up your heads, and smile;

Lift up your heads, sweet Spirits, heavily,

And make a pale light in your cypress glooms,

Tinting with silver wan your marble tombs.

In Freud’s Mourning and Melancholia, the state of melancholia is characterized by indicators such as “a profoundly painful dejection”, a “cessation of interest in the outside world”, and an “inhibition of all activity”, among other traits such as the “lowering of the self-regarding feelings to a degree that finds utterance in self-reproaches and self-revilings”. Likewise, what Freud calls “profound mourning”, that which is “the reaction to the loss of someone who is loved”, is also characterized by the “same loss of interest in the outside world” as melancholia. There exists the same “turning away from any activity that is not connected with [one’s love object]” (Freud, 2001). Both these characteristics of mourning and melancholia are present in the way Isabella treats Lorenzo— the way forgets about the world outside of him, for example. Zuniga (n.d.) goes on to describe Isabella’s exhumation of Lorenzo’s body as “a process of re-creation”. To quote Zuniga: “Isabella, through her memory and exhumation of Lorenzo’s body and ultimately placing his head inside the pot of basil, is living in the world she and her beloved had created, but that is no longer real”. Zuniga also argues that Isabella’s process of healing “culminates when the pot of basil is taken from her” and that “when Isabella dies and her laments go on, she has transcended into two realms, one in which she is happy with Lorenzo, and the other where her memory lives on through the memory of others”. It is via this dual existence that the process of mourning and melancholia, according to Freud, should be completed.

Isabella’s melancholic mourning of Lorenzo is reminiscent of the way various Pollux-figures may mourn their loved ones, seeking to (in futility) recreate or replace their lost love objects through various means. As much as I wish to expand upon this statement, I must admit that I find myself bereft of the words. Nevertheless, to elaborate more on the topic of melancholy, below are excerpts from the text Against Happiness: In Praise of Melancholy by Professor Eric G. Wilson which could potentially be used for self-reflection and Pollux astrolatry:

Unmoored from these familiar things, I am forced to look within myself, into my most mysterious interiors. Gazing within, I realize that I am ultimately alone in the world, that no one can live my life for me: not my wife, not my parents, not my culture. At this moment, when I am stripped of the familiar, I get in touch with what is most intimate: I am this person and no one else. I must find my unique potentialities, my own horizons. I must live my own life and die my own death. No one else can do this for me. […] We’ve had enough of sanders and shiners, of those who would make our ragged, rough world smooth all over. We want to lose ourselves in the mottled mixes of the botched cosmos. We want for hours to gaze at an old face in a black-and-white photo, one of those ancient pictures found in an attic and stained with rain. We wish to sit by the grizzled highway—oaks, hoary and twisted, hover at our backs—and dream of deserts broken only by bones. We finally desire to stay up very late one night and on a whim walk to the bathroom mirror. There in the glass we witness our own expression. It is, we must conclude, rather sad and worn. We smile broadly and quickly recoil. We slowly return to our normal look and find, in our heartbroken eyes, beauty. […] Melancholia empowers us to experience beauty […] the violent ocean roiling under the tepidly peaceful beams or the dark and jagged peaks that bloody the hands or those unforgettable faces, striking because of a disproportionate nose or mouth that somehow brings the whole visage into a uniquely dynamic harmony. […] Indeed, you can experience beauty only when you have a melancholy foreboding that all things in this world die. The transience of an object makes it beautiful, and its transience is manifested in its fault lines, its expressions of decrepitude. To go in fear of death is to forgo beauty for prettiness, that flaccid rebellion against corrosion. To walk with death in your head is to open the heart to peerless flashes of fire.

The excerpt above expounds beautifully the concepts of authenticity, loneliness, transiency and death in relation to melancholy. Furthermore, the book itself also includes a chapter on John Keats, a chapter I suggest people read should they be interested in the poet.

There is much more I wish to say about Castor and Pollux, such as Pollux’s association with illusory or sunken cities, of green lights at sea, of memories-as-ghosts reliving their lives at the bottom of the ocean. However, I feel a strange resistance whenever I try to write about these UPGs in an essay format. I believe that Pollux would prefer to have these things told in a more artistic or allegorical medium, and that is something I hope to do some time in the future. Until then, feel free to reach out to me if you have any thoughts or comments.

Bibliography

Ahl, F.M. (1982). Amber, Avallon, and Apollo’s Singing Swan. The American Journal of Philology, 103(4), p. 373. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/294518.

Allen, R.H. (2000) Star Names: Their Lore and Meaning. New York: Dover Publ.

Bornet, M.-A., Bernard, M., Jaques, C., Rubli Truchard, E., Borasio, G. D., & Jox, R. J. (2021). Assessing the will to live: A scoping review. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 61(4). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.09.012

Clark, B. (2000). Gemini: The Search for the Missing Twin. The Mountain Astrologer, pp. 29–35.

Collins, K. R. L., Stritzke, W. G. K., Page, A. C., Brown, J. D., & Wylde, T. J. (2018). Mind full of life: Does mindfulness confer resilience to suicide by increasing zest for life? Journal of Affective Disorders, 226, 100–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.09.043

Coucouzeli, A. (2006). The Zagora Cryptograph. Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry, 6(3), pp. 33–52.

Dandrow, E. (2021). An Unpublished ‘Medallion’ of Elagabalus from Edessa in Osrhoene: Nergal and Syro-Mesopotamian Religious Continuity?. KOINON: The International Journal of Classical Numismatic Studies, 4, 106–127. https://archaeopresspublishing.com/ojs/index.php/koinon/article/view/1113

Dreyer, E. L. (2007). Zheng He: China and the Oceans in the Early Ming Dynasty, 1405–1433. New York: Pearson Longman. pp. 148, 191–99.

Frazer, S. J. G. (2001). Myths of the Origin of Fire. Routledge.

Freud, S., Strachey, J., Freud, A., Strachey, A., & Tyson, A. (2001). Mourning and Melacholia. In The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud (pp. 243–258). essay, Vintage.

Gartrell, A. (2021) The Cult of Castor and Pollux in Ancient Rome: Myth, Ritual, and Society. Cambridge; New York ; Port Melbourne ; New Delhi ; Singapore: Cambridge University Press.

Glasberg, A., Pellfolk, T., & Fagerström, L. (2013). Zest for life among 65‐ and 75‐year‐olds in Northern Finland and Sweden – a cross‐sectional study. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 28(2), 328–336. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12062

Hankoff, L.D. (1977). Why the Healing Gods Are Twins. The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, 50, 307 – 319.

Kat, A.S. (2021) The Fourth House. Available at: https://www.alicesparklykat.com/articles/278/The_Fourth_House/

Kincaid, D. (2017) Borax: The Jewel of Midnight. SABAX Publishing.

Phengkǣo, N. (2000). Thai bān dū dāo. Samnakphim Sayām.

Ravitch, S. (2022). Astromagia. The Shining Ones: Folklore’s Spirits and Fixed Stars

Rothrauff, C. (1966). The Name Savior as Applied to Gods and Men Among the Greeks. Names, 14(1), pp. 11–17. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1179/nam.1966.14.1.11.

Santillana, G. D. (2015). Hamlet’s mill: An essay investigating the origins of human knowledge and its transmissions through myth. Nonpareil Books.

Simpson, P. (2012) Guidebook to the constellations telescopic sights, tales, and Myths. New York, NY: Springer New York.

Sullivan, E. (2000) Retrograde Planets: Traversing the Inner Landscape. York Beach, Me.: S. Weiser.

Wilson, E. (2009). Against Happiness: In Praise of Melancholy. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Wright, D. (1919) The Eleusinian Mysteries & Rites. London. Wenzel, M. (1967). The Dioscuri in the Balkans. Slavic Review, 26(3), pp. 363–381. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/2492722.

Zuniga, M. (n.d.). Mourning and Melancholia in John Keats’ “ Isabella; or The Pot of Basil.” https://www.academia.edu/29425357/Mourning_and_Melancholia_in_John_Keats_Isabella_or_The_Pot_of_Basil_

One response to ““In the dark times, will there also be singing?”: An Introduction to the Twin Stars of Castor and Pollux”

[…] The poem excerpts come from poems written by poets with Castor prominent in their charts, as expanded upon in my other blog post. […]

LikeLike