[blog post banner photo taken from the Wat Nak Prok Facebook page]

Introduction

I had initially thought to write an entire blog post focused only on nagas, including the Tibetan views on nagas, along with exploring Thai folklore on several of the famous naga kings. However, a part of me doesn’t feel ready to share these folklore yet, mostly due to questions of why am I doing this? What is my intent in sharing? Who do I intend to share this with? And, anthropological concerns about how living traditions and verbal folklore can sometimes be reduced, made ‘dead’ or ‘stagnant’ when written down onto the page, as if having it written down may codify it as being the ‘one true version’ of the folklore. I also don’t want to make myself seem like an authority on a certain topic— because I am not. I am merely a person of faith, and a practitioner who sometimes engages in magic with certain classes of serpentine spirits. If I do share folklore, it will be when I feel ready, as to make sure I don’t misrepresent my spirits or my culture. And, most likely, it will be verbally, if and when I get over my fear of public speaking on podcasts or other voice recordings.

Until then, here is a blog post that is my reflections on the visits to some naga shrines in Bangkok, Thailand, in addition to my UPG regarding Vasudhara and the fixed star Spica.

A Pilgrimage to Naga Shrines

It is no secret that I venerate and work with nagas: serpent spirits, found commonly in various Asian religious traditions. I wrote a blog post on them back in January 2022. It was actually my first ever article on this blog! So during the summer holidays of June-July 2024, when I had the opportunity to make a trip back to Thailand to visit family, I told myself that I wanted to visit as many naga shrines as I could. Usually, when one think of naga temples, the famous ones that come to mind tend to be the ones located in North Eastern Thailand (Wat Kham Chanot, for example) but since I was pretty much stuck in Bangkok for the summer due to familial and work obligations, I decided to work with what I had— naga shrines and temples located in Bangkok.

The first shrine I visited was one located literally right outside of the airport which I landed. At the four corners of the Suvarnabhumi Airport are four different naga shrines. Due to time constraints, I was able to visit one of them: the shrine to Phor Sri Suttho — a naga king famously venerated throughout Thailand, often alongside his wife, Mae Sri Pathumma. A note here too that ‘phor’ is just a term for ‘father’, whilst ‘mae’ just means ‘mother’. It is common to refer to major spirits by titles of mother or father here, or sometimes grandfather or grandmother are also used as titles. This was not my first time venerating Phor Sri Suttho. Wat Pasi temple, a temple whose monks my family give alms to weekly, also has a small shrine dedicated to Phor Sri Suttho and Mae Sri Pathumma as well. Nevertheless, the shrine at the Suvarnabhumi Airport airport was uniquely special due to the sheer number of serpent statues present at the shrine.

This is no mere decoration or accident. Serpent statues were left at the shrine as offerings. Oftentimes when one wishes to petition a spirit, like a naga spirit or naga king, it is usual to give them offerings in return. In the case of nagas, common offerings can include things like fruits, flowers, candles, incense, eggs, raw meat or, in this case, statues. From a magical or animist standpoint, I can see the statues serving as vessels for either the naga kings and queens themselves, or other serpent spirits who are a part of their retinue. The idea of offering eggs or meat to nagas may also seem wild or heretical to strict practitioners of Buddhism, who may recall that nagas—especially naga kings who have turned to Buddhism, who act as dharmapala—are not meant to eat meat due to their Buddhist vows. But, I personally would argue that not all nagas are Buddhists. It is no different to how there are folklore of the Fair Folk being vehemently against anything to do with the Christian faith, which also exist alongside other folklore of the Fair Folk wishing to be baptised. Not every spirit from the same ‘species’ holds the same religious views or opinions towards religious faith.

Having said that, a shrine-keeper (at another naga shrine dedicated to a naga king) once explained this contradiction away—why it is okay to offer nagas non-vegetarian offerings—by claiming that since naga kings have their own court, their own retinue, not every spirit serving within the naga king’s court are necessarily ‘elevated spirits’. Sometimes there are wrathful, soldier spirits who, due to their martial nature, are hungry for blood and raw meat. Thus, the offerings of raw meat that we give to the naga kings would therefore be passed along to feed these meat-eating spirits who dwelled within the naga king’s court. Again, to reiterate, I am pretty certain that something like this would be thought of as heresy by strict adherents of Mahayana, Theravada or Vajrayana Buddhism, where it may even be deemed offensive to offer meat products to nagas or other dharmapalas. But, that is the beauty of faith, of localized folk religions. This, to me, is proof of how naga worship is a living tradition, one that changes and grows based on where the worship is practiced, on who is practicing the faith.

Looking back now, in 2025, at the photos I took of the Suvarnabhumi Airport naga shrine, I realized that among the statues of serpents was a single, beautiful, statue of Phra Mae Thorani. This will be important later.

And then came the private, serendipitous events in my life which, by luck or fate, led me to visit Wat Nak Prok, a temple built in 1748 dedicated to the Buddha in the Naga Prok attitude, a depiction whereupon Buddha is seated in either the meditation or maravijaya attitude and sheltered by a multi-headed nāga. To be fair, Wat Nak Prok was always in the plans. It was easy to get to and accessible by the BTS Skytrain (the Bangkok Mass Transit System, something I sorely missed living in the UK). It was a somewhat popular tourist destination, known among Thai and Chinese tourists, although I can see it one day becoming popular among westerners as well.

The first thing that would catch one’s eyes when entering the temple is the extremely tall statue of Mucilinda Nakaraj, a naga king known for protecting Buddha from the elements after his enlightenment. According to scripture, it is said that six weeks into Gautama Buddha’s meditation beneath the Bodhi Tree, the skies darkened for seven days, unleashing a torrential rain. During this time, Mucilinda, the powerful King of Serpents, emerged from the earth and shielded the Buddha—the One who is the source of all protection—with his hood. When the storm passed, Mucilinda took on his human form, bowed respectfully before the Buddha, and joyfully returned to his palace.

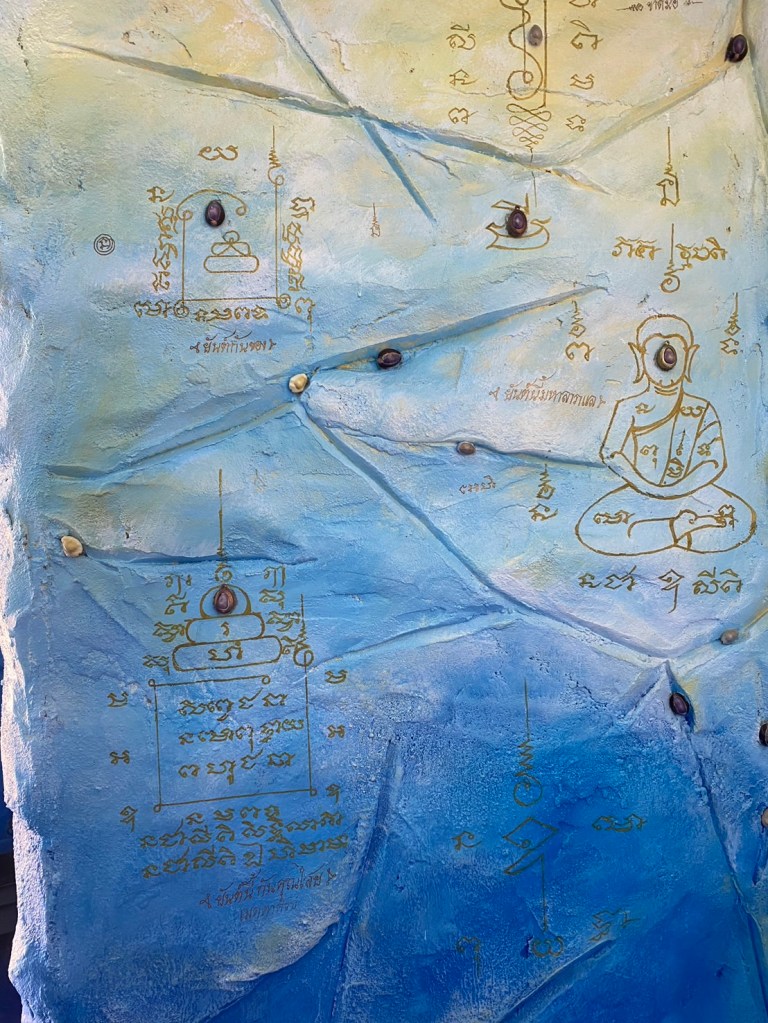

The statue of Naga King Mucalinda took my breath away with how awe-inspiring it was. But, what almost brought me to tears was the ‘cave’ underneath the statue. Wat Nak Prok had constructed a makeshift ‘underwater cave’, painted blue like flowing ocean torrent, the very walls of the cave inscribed with yantras and blessed by monks and embedded with countless ‘bia gae’: amulets made from cowrie shells, said to be able to dispel malicious sorceries and provide spiritual protection. I later would offer monetary donations to add my name to one of these shells, for the shells to be later added to the cave’s wall. Within the cave too was a small shrine to Phor Pu Sri Puchong Najaraj, another naga king, including a statue of him in his human form, whom I also paid respects to. The temple was also in the process of fixing another naga statue too and I had the opportunity to donate a ‘scale’ to be blessed and added to the serpentine body of the naga statue. There is something incredibly fulfilling to my Capricornian nature in the fact that I had the chance to help create something tangible and long-lasting as a way to show devotions to my faith.

Beyond this makeshift naga cave, however, was an actual cavern. Beneath the temple of Wat Nak Prok actually existed an old, holy (and, in my opinion, haunted in a good way) area beneath the temple. Here dwelled multiple objects of interests, from beautiful statues to various deities, to the ‘luk nimit’ which is a spherical stone ball, adorned with gold leaf, symbolizing the demarcation of sacred boundaries, marking the area as being sanctified. But, what truly drew me in, was the so-called hole of water that is said to be connected to the naga underworld. The temple encourages you to offer holy water to the hole, and I also see countless coins being thrown into the hole too, so I did the same. I also discreetly collected some of the water for personal (spiritual and magical) use, and purchased a few naga-themed amulets that the temple sells. Some of these include the classic naga ‘fang’ amulet and a talismanic Naga-Rahu coin that has gone through rounds and rounds of blessings by monks across the country (including being blessed at Kam Chanod, another famous holy site for nagas), made from an 275-year old iron nail, taken from the temple’s doors.

I did not take photos of the underground area with the luk nimit and the water hole due to it feeling inappropriate to do so. I did, on the other hand, take plenty of pictures of the statue of Naga King Mucalinda and the bia gae cave.

There are many, many other things I could go on endlessly about regarding Wat Nak Prok, such as their Rahu ceremonies and Saturn holy water which I was lucky to get my hands on for remediation purposes, or their other humongous shrine and statue of Thao Wessuwan/Vaiśravaṇa (who I believe deserve his own blog post, one indeterminate day in the future). However, the life-changing experience I had at Wat Nak Prok, surprisingly, had not much to do with nagas. It, instead, had everything to do with a goddess: Phra Mae Thorani.

Phra Mae Thorani, or Vasudhara

Depictions of Phra Mae Thorani are frequently found in shrines and Buddhist temples across Burma, Cambodia, Thailand, and Laos. In Buddhist mythology, she is represented as a young woman wringing water from her hair to submerge Mara, the demon who attempted to tempt Gautama Buddha during his meditation beneath the Bodhi Tree. Phra Mae Thorani is also important in Buddhist lore, where in Laotian and Thai depictions of Gautama Buddha, the ‘touching the earth’ mudra, also known as the Maravijaya Attitude, signifies the Buddha calling upon Phra Mae Thorani as a witness to his past virtuous deeds. By pointing toward the ground, he seeks her aid in overcoming obstacles on his path to enlightenment.

In Thailand, Phra Mae Thorani is thought to be a chthonic deity, a earth-and-water goddess associated with the very land itself. The most well-known shrine of hers in Bangkok is probably the one at the corner of Sanam Luang park. She, at least at Wat Nak Prok temple, is also known to help worshippers buy and sell lands, turning land into wealth and money. The depiction of Phra Mae Thorani at Wat Nak Prok temple, unlike at other locales, differ in that here, she is shown to be standing beneath the hood of a naga, squeezing water from the braids of her hair, the water turning into a stream of jewels and gold coins. I personally have never seen such an interpretation of Phra Mae Thorani before— standing beneath the hood of a naga. Wat Nak Prok itself promotes this depiction of hers to be something that can only be found at this specific temple, a specific form of her venerated here especially. But it makes sense, when you think about it. Nagas are associated too with the land and the waters and with wealth.

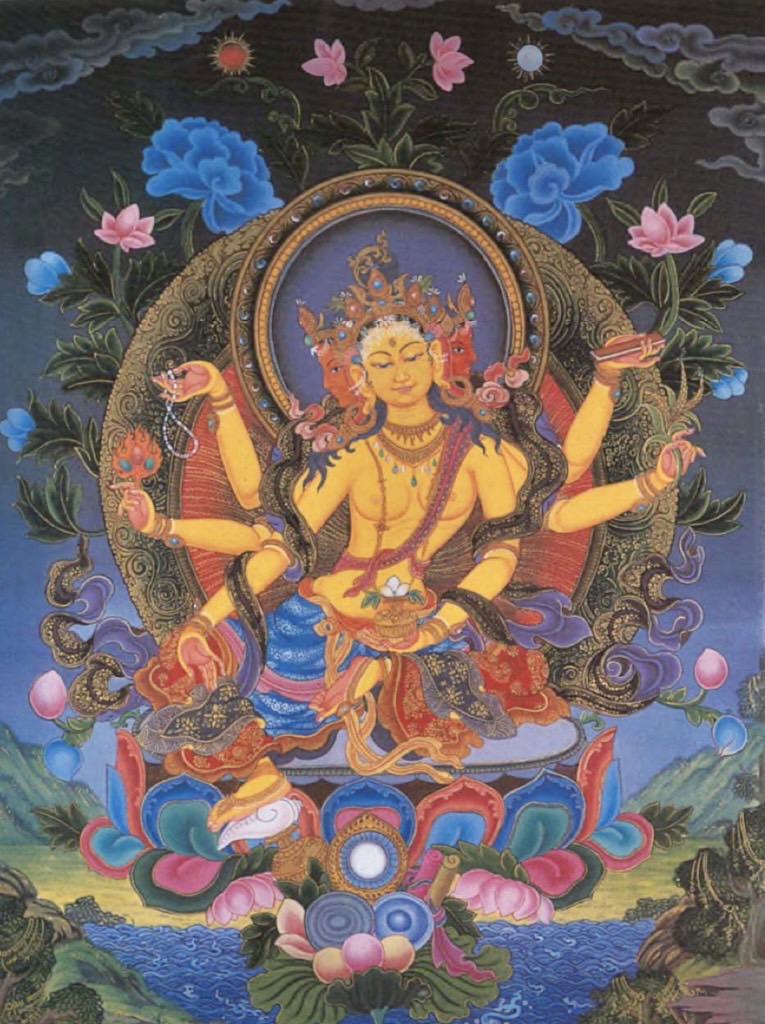

One other important fact about Phra Mae Thorni is how she is also known by another name: Phra Sri Vasundhara, whose name is rendered in some contexts as Vasudhara. It would take a long time to explain the intricacies of her appearances in Indian Hindu-Buddhist faith and Tibetan Buddhism. The gist of it is that she is the Bearer of Treasure, a wealth goddess of sorts (although I would be hesitant to pigeonhole her as being just a wealth goddess). According to the book Buddhist Goddesses of India by Miranda E. Shaw, her primary role as a bestower of bounty is seen in her epithets as “Wish-Fulfilling Tree” (Kalpa-vrksã), “Perfectly Generous One” (Dana-pãra-mitã), “Giver of Wealth” (Dhanam-dadã), “Dispenser of Riches” (Ratnadhãtã), “Lady Who Rains” (Varsani), “Maker of Good Fortune” (Srikari), “Great Wish-Granting Jewel Goddess” (Cintamani-mahädevi), “Lady Who Delights in Currency and Storehouses of Rice” (Dhanyagaradhana-priyã), and “Supreme Ruler of the Realm of Opulence” (Ratnadhätvisvaresvari’s).

Vasudhãra’s blessings extend beyond material wealth, however, as she grants both outer and inner riches. In the Buddhist wisdom tradition, knowledge is among life’s most valuable treasures, with wisdom serving as the key to spiritual liberation. Therefore, the goddess who bestows all that is precious is also endowed with the names “Bearer of Knowledge” (Vidyadhari), “Embodiment of Perfect Wisdom” (Prajña), “Bearer of Truth” (Dharma-dhãrini), “Foremost among Bestowers of Knowledge” (Vidyadãna-isvaresvari), “Knowledge Incarnate” (Jñānamurti), “Glorious Increaser of Enlightened Ones” (Sri Buddha-vardhini), and “Revealer of Buddhist Paths” (Darsani Buddha-marganam). In the Buddhist perspective, wealth and gnosis are not inherently at odds, as prosperity can support both individuals and institutions dedicated to the pursuit of wisdom.

More than that though, is the gnosis I received: that Vasudhara is related to the fixed star Spica.

Vasudhara is also known as Gold Tara, one of the 21 Taras commonly venerated in Tibetan Buddhism. Her iconography is incredibly detailed and I could spend a long time explaining each of the little symbolism depicted in her image. What is important though is her golden skin— a color linked to wealth, fertile soil, the harvest season, and precious metals. Notably, one meaning of vasu is ‘gold’. To cite Miranda E. Shaw once more, in Tantric symbolism, yellow represents the earth element and embodies generosity—one of the five fundamental qualities of Buddhahood, signifying the transformation of greed into infinite charity. What stands out to me as well is the sheaf of grain (the dhanya-mañjari) she holds in her left hand. This iconographic detail highlights Vasudhara’s connection to agriculture, for in an agrarian society, a plentiful harvest is not only essential for sustenance but also a key source of wealth. The plant she holds may represent grain in general or rice specifically, both referred to as dhanya. As a grain-bearing goddess, she is praised as the “mother of all beings” (bhūta-mātā), “one who holds motherly affection for her devotees” (bhakta-vatsalā), and the “universal mother” (sarvatra mātṛkā), fulfilling her maternal role by fecundating crops to nourish and prosper her children.

Spica, one of the Behenian fixed stars. The term Spica comes from Latin which translates to ‘Ear of Grain’. It is the alpha star of the constellation Virgo— the Virgin. This is the constellation which Marcus Manilius, in his 1st-century Roman work Astronomicon, associates with Demeter, the Greek goddess of agriculture, grain and bread, she who sustained mankind with the earth’s rich bounty. From this, it is not hard to see why Spica may be interpreted to be an emanation of the wealth-and-grain goddess, whether that be Vasudhara or whomever. This is a UPG which I have confirmed via divination, both my own and double-checking with that of trusted diviners. There have also been plenty of other astrologers and occultists out there who have written articles on Spica, some of my favorite posts being from Mahigan of Kitchen Toad (here and here) and Orphic Astrology (here), so I recommend that you read those if you are interested.

Moreover, earlier in January 2025, the 27th Chogye Trichen Rinpoche, the co-head of Tsapra sub-school of Sakya Tradition, had bestowed empowerments with lungs to those seeking to take Vasudhara as their yidam deity, to venerate and perform practices with her. For those unfamiliar with Tibetan Buddhism, you can think of an empowerment being both the permission one receives from a lama to perform certain prayers and rites. It involves following along with some meditative visualizations, committing to certain vows and, in return, receiving the body, speech and mind blessings so you can effectively practice what you wish to practice. This wasn’t my first foray into Tibetan Buddhism so I came prepared, and was lucky enough to be able to attend this live and receive the empowerment, for which I am grateful.

Spica means many things to me. More than mere material wealth (not that there is anything wrong with appreciating the beauty and riches of the material world), Spica is love. She is the boundless, infinite ocean of love, in contrast to the manufactured scarcity of capitalism. She is the embodiment of generosity, teaching me how to keep an open heart despite the risk and pain that trusting others may bring. She is also wisdom, or what some may call spiritual wealth, something I am hoping to cultivate throughout my life. She is the solidness of the earth, grounding and dependable. She is honey and sweet waters and warm rays of sunlight. She is the richness of the soil, the relief of cool rains, fecundity in all its creative forms.

For now, my Spica-Vasudhara practice remains simple, consisting of me,at the minimum, giving weekly offerings to the star and deity, and trying to perform a 108-mantra recitation of the deity’s name whilst anointing myself with Spica oil (shoutout to Haus of Ophidious!). It is not much, nothing too fancy, but it comes from the heart, it comes from devotion— and that, as I’ve come to learn, is enough.

To the left, Vasundhara Devi by Lok Chitrakar, to the right, Vasudhara by Amrit Karmacharya

Conclusion

In a time when the world feels like it is full of evil, full of hate, the nagas, and Spica herself, reminds me that there is love in the world, that there will always be love in the world. I would like to end this post by wishing that everyone take care of themselves, that everyone be kind to themselves. It may be rough out there, all the cruelty and greed and heartlessness, but that does not negate the warmth and benevolence that also exist in this world— that will continue to always exist in this world.